Editor’s note: The illicit drug trade is undergoing a seismic shift, with Utah in the middle of the deadly impact of opioids. This is another in an ongoing series of stories about this modern-day plague.

Editor’s note: The illicit drug trade is undergoing a seismic shift, with Utah in the middle of the deadly impact of opioids. This is another in an ongoing series of stories about this modern-day plague.

SALT LAKE CITY — In November, when President Trump’s bipartisan commission on the opioid crisis issued its report, it recommended 54 solutions but put particular emphasis on two things: expanding access to medicine that helps addicts and creating more drug courts.

First introduced in 1989, drug courts are widely considered one of the nation’s most successful approaches to helping addicts get clean and stay out of jail. Utah’s drug courts have long been heralded as a national model.

But despite the program’s effectiveness, in Utah, the number of addicts participating in drug court fell by 10 percent between 2015 and 2017, according to the state’s Department of Human Services’ Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health.

A Deseret News review of drug courts in all 50 states has revealed that Utah is not alone. Although the number of drug court programs across the country is on the rise, the enrollment of addicts in some states has fallen.

This is happening at a time when the nation’s opioid crisis is reaching pandemic levels. Last year, 64,000 people died from opioid overdoses in the United States — that’s more than the number of American lives lost in the entirety of the Vietnam War.

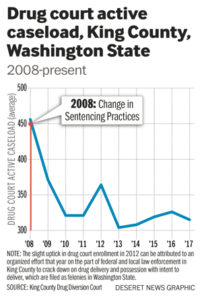

In the state of Washington’s King County, drug court enrollment has decreased by 34 percent since 2008 – from 456 to an average of 300 active cases, says Mary Taylor, King County Drug Diversion Court coordinator.

Participation in California’s drug court program has plummeted by as much as 50 percent since 2014, according to Mike Hestrin, Riverside County district attorney.

The drop in enrollment in drug courts is an unforeseen consequence of a well-intentioned effort to tackle the nation’s exploding opioid crisis: lighter sentences for drug offenders.

In the past, getting caught with a baggie of heroin could result in a felony drug possession conviction and a sentence of up to five years. But thanks to Utah’s 2015 Justice Reinvestment Initiative, heroin and other drug possession convictions have been downgraded to misdemeanors or citations, carrying little to no jail time.

“This trend is concerning because the program is highly effective,” says Dr. Anna Lembke, chief of the Stanford University Addiction Medicine Dual Diagnosis Clinic. “For many of my patients, their only period of sustained sobriety was while enrolled in drug court.”

The Justice Reinvestment Initiative — also implemented in 26 other states — has been praised as a forward-thinking solution to a host of criminal justice problems, including the overcrowding of jails.

Reducing sentences for drug offenders reserves jail beds for violent offenders and others the court deems likely to commit major crimes. Fewer inmates means lower prison costs, freeing up state dollars to reinvest in treatment programs and other long-term solutions to criminal activity.

But what few policymakers saw coming was that by removing the threat of a felony conviction and a long stint in jail, the initiative inadvertently reduced the incentive for offenders to choose to participate in drug court.

Drug court is a 12-18 month intensive, court-supervised program involving counseling, frequent drug testing and sanctions for those who slip up. In order to be admitted, offenders must plead guilty to the crime of which they were accused. Those who graduate have their guilty pleas withdrawn and criminal charges dismissed.

It was an attractive alternative for someone facing a five-year sentence and a felony conviction on their record, says Brent Kelsey, assistant director of the Utah Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health. But when the jail sentence is just a few days or months, people are less likely to choose drug court.

“If they are facing a misdemeanor charge, it might mean a shorter jail stay,” says Kelsey. “There’s not much incentive for them to participate in a long, structured program.”

A chance to be a father

Utah has only enough state funding to treat about 15,000 of the estimated 134,000 people who need substance abuse treatment, the majority of whom are unemployed and uninsured. Thus, for many, especially low-income substance abusers, the criminal justice system is the only way to access and afford treatment.

“The criminal justice system plays a huge role in getting people into recovery,” says Lembke.

But in the past three years, nearly 200 available Utah drug court spots have been left unfilled. That’s 200 missed opportunities for addicts to access drug court — a program Trevor Cook says changed his life.

Now 36, Cook grew up in Kamas, Utah. His father abandoned his family when he was a baby, leaving him with an emotional void so vast he felt that nothing could fill it. He suffered from severe anxiety, depression, anorexia and bulimia, and started using drugs at the age of 12.

“By the age of 15, there wasn’t a drug I hadn’t tried,” he remembers. “At 16, I was a full-blown addict.”

Cook abused cocaine, meth, prescription opiates, bath salts and alcohol throughout his 20s, even after marrying his wife with whom he had a son and two daughters. After a few too many drinks, he would often get behind the wheel and black out, waking up bloody and freezing hours later, unable to recall what had happened.

In 2012, after his third felony DUI charge, Cook opted for drug court. He says the program was the “hardest thing I’ve ever had to do,” but with the judge, prosecutor, attorney and therapist holding him accountable, he was able to graduate and get sober for the first time in 17 years.

Cook now works full-time as a peer recovery coach at Utah Supports Advocates for Recovery Awareness, an addiction recovery community in South Salt Lake.

In 2013, Cook and his wife — who still struggles with alcoholism — split up, and he has been raising his three children on his own. He recently proposed to his girlfriend, Sharlee, and is looking forward to their wedding this coming fall.

“Because of drug court, I can be the father my kids deserve,” he says.

New drug court options

Other states are also seeing a decline in drug court participation.

Lembke of Stanford says that after the implementation of Proposition 47 and other legislation reducing sentences for drug offenses the California drug court program “lost its teeth,” and drug courts “virtually emptied out.”

“We lost our leverage as prosecutors, so our drug court programs essentially died after Proposition 47,” says Hestrin. “It’s sad, because I truly believe our drug courts helped people suffering from addiction, and now they are back on the streets and there’s nothing we can do for them.”

Taylor says she has noticed the same thing.

“It’s been troubling to see the decline in participation, because this is a program that really works,” says Taylor. “Drug courts are able to do battle with the drugs that have taken an addict’s brain hostage, and allow them to take a break long enough to see if they really want to live the way they are living.”

According to Taylor, King County drug courts experienced a dramatic drop in referrals since 2009 because of a series of reforms that reduced sentences for drug possession and low-level dealing.

“There are many people arrested for drug possession that have serious problems and need help and now, because of this, they are less likely to get those services,” explains Douglas Marlowe, scientific research consultant for the National Association of Drug Court Professionals. “I’m fearful that a lot of these well-intended policies may reduce our overemphasis on incarceration, which is a good thing, but ignore the needs of that population, which is a very bad thing.”

Though Kelsey and other experts agree on the powerful influence of sentencing changes on the decline of Utah’s drug court enrollment, other factors have also played an additional role. For example, participation in the San Juan County’s drug court program fell due to the court’s inability to fill two staff positions.

Rick Schwermer, Utah state court administrator, says the contribution of drug court is so critical that police departments and judges have started to make changes to drug court eligibility so that more people can enter these programs.

“There are still plenty of people who are appropriate for drug court and would benefit from the program,” says Schwermer. “But because of the Justice Reinvestment Initiative, it’s not as easy to find them as it used to be, so we have to more creative about who we can include in drug court.”

Some drug courts in Utah have opened their doors to those who have committed not only drug offenses but other crimes in which drugs were a motivating factor — credit card fraud, forgery, burglary or domestic violence — that still carry felony charges and longer sentences.

10 comments on this story

Drug court numbers are expected to start going up again in the next year, says Kelsey.

Lembke says every effort should be made to incentivize offenders to participate in drug court.

“The people at the high level making these policies think it’s wonderful that we’re not criminalizing addiction,” she says. “But if the criminal justice system has no leverage to compel addicts to get treatment, we will see a big drop in the number of people who are able to resolve their drug and alcohol problems.”