June was another rough month in Manchester, N.H. Over the course of 30 days, there were 99 suspected opioid overdoses, six of which were fatal. That’s the most overdoses in a month so far in 2017, according to Christopher Stawasz, regional director of emergency medical services provider American Medical Response.

June was another rough month in Manchester, N.H. Over the course of 30 days, there were 99 suspected opioid overdoses, six of which were fatal. That’s the most overdoses in a month so far in 2017, according to Christopher Stawasz, regional director of emergency medical services provider American Medical Response.

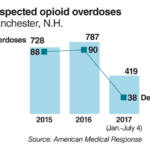

It’s the continuation of a dangerous trend for any city, let alone one with a total population of 110,000. From January to July 4, there were 419 suspected opioid overdoses, compared with roughly 400 for the same period last year. And for all of 2016, there were 787 suspected overdoses, 90 of which were deadly, according a report issued by Mayor Theodore Gatsas.

Similar to their counterparts in Colorado, Ohio, Washington—or anywhere in the nation, for that matter—public health leaders in Manchester are searching for any innovative intervention that can help turn the tide. They may have found one.

Last April, after a paramedic helped a colleague’s relative get treatment for his addiction, the city launched the Safe Station Program. Now, all 10 of Manchester’s firehouses are a safe haven where people struggling with addiction can seek assistance. Paramedics are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, to conduct a full medical evaluation before transporting the patient to a local hospital’s emergency department or a treatment facility.

Last April, after a paramedic helped a colleague’s relative get treatment for his addiction, the city launched the Safe Station Program. Now, all 10 of Manchester’s firehouses are a safe haven where people struggling with addiction can seek assistance. Paramedics are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, to conduct a full medical evaluation before transporting the patient to a local hospital’s emergency department or a treatment facility.

The process takes less than 15 minutes, Stawasz said. That’s compared to the weeks or even months it sometimes takes to get treatment. A recent New England Journal of Medicine study showed that only 21% of people addicted to opioids in the U.S. received any treatment between 2009 and 2013.

“You’ve got a very small window of time when people are willing to go for that help,” Stawasz said. “The beauty of this program is that it captures them when they are most willing to get the help, and it gives it to them very quickly.”

From May 2016 to June 2017, more than 1,800 people sought help through Safe Stations. All of them went to either an emergency room or treatment facility. There is no threat of arrest or judgment, according to those running the program. The program has been credited with reducing the number of emergency calls due to overdose by 30%, according to Stawasz.

It’s been so successful that the seven fire stations in Nashua, N.H., adopted the program last November. Nashua has its fair share of problems, too: 31 opioid overdoses resulting in four deaths in June and a 28% jump in suspected opioid overdose deaths between January and June. Between November and June, 576 people made use of the Nashua Safe Station program.

On the other side of the country in northwest Washington state, public health officials are taking an equally unorthodox approach to combating an opioid crisis.

“In this epidemic that’s spiraling out of control, we should take advantage of every tool that we possibly can,” said Dr. Jeff Duchin, public health officer for King County, Wash.

Last year, Duchin co-chaired a task force created by Seattle Mayor Ed Murray to address the opioid epidemic. One controversial recommendation was to set up sites where drug users, under supervision of a health professional, could inject illegal drugs. The idea is to not only monitor the addict, thus lowering the risk of an overdose, but also connect them with treatment when they are ready. The site would also provide sterile needles to reduce the spread of infectious diseases such as HIV or hepatitis through shared needles.

About 100 such sites currently operate in more than 60 cities around the world.

Federal and state laws prohibit safe injections sites in the U.S., but some cities are considering them and the American Medical Association’s House of Delegates in June voted to endorse some safe site pilot programs. The Massachusetts Medical Society is also supportive. MMS President Dr. Henry Dorkin said safe injection sites have worked in other countries. The organization began examining applying the same approach in the U.S. after other more widely accepted actions such as needle exchanges and naloxone failed to reverse the rising number of overdose deaths. City leaders in Philadelphia, San Francisco and Ithaca, N.Y., have all proposed them—while raising concerns over the perceived acceptance of illegal behavior.

FB02LStudies of sites in Australia, Germany and the Netherlands show reductions in overdoses, crime and risky behaviors.

“There is still this fundamental, ingrained thought that it’s just something about the person and it’s not an illness,” said Dr. Michal Frost, director of internal medicine at the Horsham Clinic, a behavioral health facility in Ambler, Pa. He believes that’s stifled innovation.

Indeed, the last new opioid addiction treatment approved by the Food and Drug Administration was buprenorphine in 2002. The drug had been on market since 1981 when it was first used as a pain-relieving replacement for morphine. Naltrexone, which commonly goes by the brand name Vivitrol or Revia, has been approved as a treatment for heroin since 1984, and methadone has been in use since the late 1940s.

Most new medications are simply a variation in the way buprenorphine, naltrexone, naloxone or some combination of those compounds, are delivered.

Frost said there’s been research to develop a vaccine that could use the body’s own immune system to nullify the effects of opioids, but that innovation is years from being ready for use.

Patient advocates hope that President Donald Trump’s policies will cut regulations that tie doctors’ hands in treating addiction and support new ways to make maintenance treatment more accessible. Thus far, the administration’s most visible step has been creating a panel tasked with evaluating new and proven options. The commission missed its deadline to submit an initial report recommending federal approaches that can be taken to combat the opioid epidemic.