Across the country, the number of youth who are incarcerated is down.

Across the country, the number of youth who are incarcerated is down.

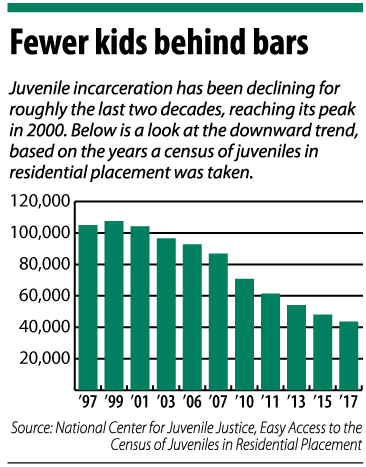

In 2017, 43,580 minors were incarcerated, a 4 percent drop from 2016. Compare those numbers with 2001, when 104,219 juveniles were detained – 58 percent more than in 2017.

Juvenile incarceration peaked in 2000, according The Sentencing Project, and has been on a downward decline nationally since. Indiana is following the trend, now housing fewer than 1,600 juveniles in residential facilities, compared to more than 3,200 in 2001, according to the Department of Justice.

This decline, juvenile justice experts say, represents both a policy shift and a shift in mindset. The latter actually came first – stakeholders began thinking of juvenile justice as a public safety issue, and that has translated into policies designed to rehabilitate young offenders rather than punish them.

Of course, advocates say there are more reforms they’d still like to see. But they’re also applauding this mindset shift as positive for juveniles and for the public welfare.

National decline

The decline in juvenile incarceration aligns with recent research showing detaining juveniles does more harm than good. Most literature now accepts the proposition that human brains are not fully developed until the mid-20s, so detaining minors can have a negative impact on their minds, especially for young people who have mental illnesses.

Indeed, during the 2019 session of the Indiana General Assembly, lawmakers attempted to pass legislation that would allow children as young as 12 to be waived into adult court for attempted murder. The legislation came in response to the May 2018 shooting at Noblesville West Middle School – where the 12-year-old shooter could not be charged as an adult for wounding a teacher and a classmate – but the legislation received serious opposition from juvenile justice advocates. Eventually, it was defeated.

Karozos

KarozosWith this new research as a backdrop, reform advocates say they are pleased to see society taking a different view of how minor offenders should be treated in the criminal justice system. Amy Karozos, director of the Indiana Public Defender Council’s Juvenile Defense Project, contrasted the current societal view to the view of juvenile crime in the 1990s.

During that decade, the idea of juveniles as “super predators” caught on. The thought then was that there were some minors who were beyond rehabilitation. In response, new legislation emerged that encouraged a “tough on crime” policy as it applied to kids.

Juvenile crime peaked in the 1990s, Karozos said, but since then it has followed the decline of juvenile incarceration.

Youthful indiscretions

Rovner

RovnerThe decline in juvenile detention and crime go hand-in-hand, said Joshua Rovner, a senior advocacy associate for The Sentencing Project who works on juvenile justice issues. When young offenders are sent to alternative services or treatment programs, rather than housed in a correctional facility, they’re less likely to come into contact with more hardened offenders, Rovner said.

He gave an example he once heard from a judge in Georgia: two juveniles – one who stole a car and one who skipped school – were both sent to a detention center. The juvenile who had stolen a car already knew how to skip school. But, the judge said, the juvenile who skipped school was introduced to a more serious offender and, thus, learned how to steal a car.

“One of the main reasons that young people get into trouble is because of their peer group,” Rovner said. “… If you send a kid to a juvenile detention center for vandalism or for skipping school, as happens in many states, that’s now changed the peer group.”

Hessler

HesslerSean Hessler, a former juvenile crimes prosecutor who now handles juvenile delinquency as part of his criminal defense practice, agreed that youngsters today are now being charged with crimes for acts that, when Hessler was a kid, would have been dealt with at school or home.

Hessler remembers once, when he was a kid, he and his friends got into a mud fight outside their school and made a mess. Their punishment was to clean up the mess and apologize, but that kind of act today could end with a charge of disorderly conduct.

“Just for a youthful indiscretion,” he said. “There’s no need to criminalize that.”

Finding alternatives

Wever

WeverSo if criminalizing “youthful indiscretions” can negatively impact kids, how should their misdeeds be handled? In Indiana, that question is largely being answered through the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative, or JDAI.

Contrary to its name, JDAI address more than juvenile detention, Indiana JDAI director Nancy Wever said. It’s a holistic approach that engages community stakeholders to provide young offenders with the services they need to divert them from the criminal justice system.

JDAI is currently live in 32 Indiana counties. Among those counties are LaPorte, where Judge Thomas Alevizos said he is likewise seeing a decline in juvenile crime. Rather than sentencing kids to a detention center, Alevizos said his county has used alternatives, such as creating an after-school program that keeps at-risk juveniles off the streets and an intervention program that can avert a juvenile’s arrest.

One of the keys to JDAI, Wever said, is its data-driven approach. Alevizos agreed, noting the data has shed light on shortcomings in LaPorte County’s juvenile justice system.

Alevizos

AlevizosFor example, Alevizos said the county once learned it was charging juveniles with escape, when the child was actually just using their GPS monitor in their front yard or on the front porch. The monitor might read that as an escape, the judge said, but such an offense is not worth sending a child to a detention center.

“The idea is that you use less coercive options,” the judge said. “You want to dissuade them from progressing further in the system.”

Future reforms

There are several ways a court can keep a child from progressing through the system, the juvenile justice advocates say. Hessler has had clients sent to a horse farm, where they are tasked with taking care of the animals. Such programs teach the values of hard work and teamwork, Hessler said.

In general, the attorneys agree that unless a juvenile is a flight risk or presents a serious risk of harm to themself or others, detention should be the last choice, not the first.

In general, the attorneys agree that unless a juvenile is a flight risk or presents a serious risk of harm to themself or others, detention should be the last choice, not the first.

While the available alternatives are making positive improvements, the advocates say there are additional changes they’d still like to see.

Karozos, for example, would like there to be a floor to detention. Generally, the floor to the Department of Correction is 12 years old, she said, and she’d like to see that floor extended to all juvenile detention. Her group has also been advocating for better representation of juveniles at their detention hearings. And more generally, Wever said JDAI is working to cut down on racial disparities in juvenile arrests and incarceration.

Making further change, Rovner said, will require an even deeper mindset shift. He likened such a shift to the changing judicial view of people with drug addictions — rather than treating them like criminals, courts are now providing more opportunities for drug offenders to seek recovery options.

While kids might break the rules and even the law, Rovner said such situations should be viewed in light of typical preteen and teen behavior.

“That sympathy for drug users really ought to be extended,” he said. “… For ordinary adolescent behavior, we don’t need to send them to juvenile courts.”•